The Tabata workout might just be what you are looking for when time is short. This is where science offers some good answers. Unfortunately, fitness trainers are generally clueless about the science of fitness. Most workouts are over done and cause more harm than good. What you really should know is the exercise ‘sweet spot’ – i.e., the frequency, intensity, and duration that provide optimal fitness.

The Tabata workout might just be what you are looking for when time is short. This is where science offers some good answers. Unfortunately, fitness trainers are generally clueless about the science of fitness. Most workouts are over done and cause more harm than good. What you really should know is the exercise ‘sweet spot’ – i.e., the frequency, intensity, and duration that provide optimal fitness.

A little known study by Japanese researcher Professor Izumi Tabata, published about a decade ago, nails it. His work is now popularly referred to as a Tabata workout. The original study shows how to get maximal results from a 4-minute workout, no more than 5 days a week. Here is what you should know about his research on achieving maximal fitness is less time than ever.

SIDENOTE: I have a major caveat about what fitness really means, though, which I have outlined at the end of this post. It is a crucial consideration, so be sure to at least take a quick look at what I have to say.

Defining Fitness

It might surprise you to know that there is no general agreement on how to define fitness. Even the most complete definitions of fitness, such as here on here on Wikipedia, are oversimplified and vague. In the absence of a clear and concise definition, how can anyone help you design an effective fitness program?

Everyone who is anyone in health and fitness cites the importance of exercise. Advice on what that exercise should be, unfortunately, is all over the map.

Part of the problem is that different research studies use any of a number of indicators for measuring physical changes that may be components of fitness. For the moment, let’s focus on two of these:

- Maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max), which reflects aerobic fitness

- Anaerobic capacity, which reflects performance in short duration, high intensity activities that do not depend on oxygen

These are the two indicators of fitness that Prof. Tabata used in his original research study. Anyone who seeks better fitness should select a workout that improves both their VO2max and their anaerobic capacity.

First a Warning About the Tabata Workout

Searching on Tabata protocol or Tabata workout on Google will give you a gazillion results. After you read this post, though, you will be able see that 90 percent of what folks are telling you about how to do a Tabata workout is wrong. Videos, websites, articles, books … my warning is that there’s lots of crapola to ignore.

I will comment on this problem after you see what the protocol actually is, as described and correctly adapted from the original research by Prof. Tabata on Japanese Olympic speedskaters. This may seem like a lot of scientific gibberish to most folks. So I have highlighted the most important parts, which I expand on below.

Now for the Real Thing

Can you believe that it only takes 4 minutes to max out both VO2max and anaerobic capacity? That’s what a Tabata workout has been known for since the original research on it was published in 1996.

Too hard to believe?

Let’s take a look under the hood of this discovery and what you can get out of it. You CAN do this at home if you know what you are doing.

Now let’s see how phenomenal it really is.

It started with Japanese speedskaters.

What we know from them is that you can quit wasting time in the gym when you can get what you want in 4 minutes or less.

The Research

Here are the reference and abstract of the original research article, with highlights to emphasize the take-home message.

REFERENCE:

Tabata, I., Nishimura, K., Kouzaki, M., Hirai, Y., Ogita, F., Miyachi, M., and Yamamoto, K. (1996). Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2max. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 28(10): 1327–1330.

ABSTRACT:

This study consists of two training experiments using a mechanically braked cycle ergometer. First, the effect of 6 wk of moderate-intensity endurance training (intensity: 70% of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), 60 min/d, 5 d/wk) on the anaerobic capacity (the maximal accumulated oxygen deficit) and VO2max was evaluated. After the training, the anaerobic capacity did not increase significantly (P > 0.10), while VO2max increased from 53 +/- 5 ml/kg/min to 58 ± 3 ml/kg/min (P < 0.01) (mean +/- SD). Second, to quantify the effect of high-intensity intermittent training on energy release, seven subjects performed an intermittent training exercise 5 d/wk for 6 wk. The exhaustive intermittent training consisted of seven to eight sets of 20-s exercise at an intensity of about 170% of VO2max with a 10-s rest between each bout. After the training period, VO2max increased by 7 ml/kg/min, while the anaerobic capacity increased by 28%. In conclusion, this study showed that moderate-intensity aerobic training that improves the maximal aerobic power does not change anaerobic capacity and that adequate high-intensity intermittent training may improve both anaerobic and aerobic energy supplying systems significantly, probably through imposing intensive stimuli on both systems.

The Key

The first highlighted sentence is the workout: 4 reps of 20-second maximal intensity with a 10-second rest. One rep after another, for a total of 8 reps, adding up to a combined total of 4 minutes.

That’s it!

This study was done on Olympic-level speedskaters in a lab. Just in case you don’t have the equipment to measure your effort level (maximal here is defined as “170 percent of VO2max”), here is what you can do: GO ALL OUT.

Take your pulse if you want (after the 8th rep), assess how much you gasp, whatever gives you some indicator of your intensity. You will know what all out feels like. It is a 20-second killer.

In my case, I use a stationary bike at LA Fitness. My standard sprint interval training workout before Tabata was 8 reps of 1.5 minutes at ca. 15-16 mph, with a 2-minute rest (7-8 mph) between reps. My Tabata-level intensity is 21-22 mph for 20 seconds, followed by complete stoppage for 10 seconds. My gasping level, on a scale of 1-10, is absolutely a 10.

The key is all-out, maximal effort.

Results

Tabata compared a maximal-intensity group with a group that pedaled for an hour at 70 percent of VO2max, also 5 days a week for 6 weeks.

If you are doing the math, the maximal-intensity group worked out for 20 minutes a week, while the ‘endurance’ group worked out for 5 hours a week.

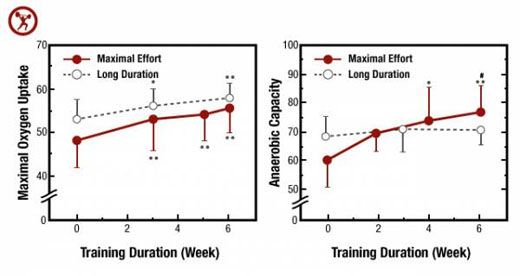

Here is what the results looked like for both groups in graphic form (explanation below):

(Graph thanks to Craig Marker at BreakingMuscle.com.)

In the above figure, the graph on the left shows the results of oxygen uptake. It is a measure of aerobic efficiency. The solid red line is the maximal-intensity group while the dotted black line is the endurance group.

Both groups improved their aerobic efficiency more or less equally (i.e., no statistical difference). This result was expected for the endurance group since they were specifically training for this goal. The results of the maximal-intensity group, however, came as a big surprise.

The graph on the right shows a measure of the anaerobic process. As expected, the maximal-intensity group improved their performance while the endurance group did not. This makes sense given that maximal intensity uses a lot more anaerobic processes, which therefore should become more efficient with this training.

Ultimately, the 4-minute maximal-intensity workouts had better anaerobic benefits as well as the same aerobic benefits as the endurance workouts.

ABSOLUTELY SHOCKING!

It still is.

Sage Advice

Clearly the maximal-intensity Tabata workout is, well … intense. Be smart about it if you are not already at least a little bit in shape. That is my pseudo-medical advice.

In addition, although Tabata’s study was done with world-class athletes 5 days a week, that would be very stressful for you or me. Too much high-intensity exercise is counterproductive and even destructive.

For us weekend warriors, no more than 2-3 workouts a week are plenty. This frequency is especially important if you, like me, also do a once a week Body by Science style weight-lifting workout (the BEST ever!). See what that means here: Building Muscle As You Age – Exercise.

An Important Heads Up

Comparison groups are very informative, such as what Tabata used in his original 1996 study. Another comparison study followed in 1997, which gives you an important heads up for getting the most out of a maximal-intensity workout. Here are the citation and abstract, with the important part highlighted for simplicity:

REFERENCE:

Tabata I., Irisawa K, Kouzaki M, Nishimura K, Ogita F, and Miyachi M. 1997. Metabolic profile of high intensity intermittent exercises. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 29(3): 390-395.

ABSTRACT:

To evaluate the magnitude of the stress on the aerobic and the anaerobic energy release systems during high intensity bicycle training, two commonly used protocols (IE1 and IE2) were examined during bicycling. IE1 consisted of one set of 6-7 bouts of 20-s exercise at an intensity of approximately 170% of the subject’s maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) with a 10-s rest between each bout. IE2 involved one set of 4-5 bouts of 30-s exercise at an intensity of approximately 200% of the subject’s VO2max and a 2-min rest between each bout. The accumulated oxygen deficit of IE1 (69 +/- 8 ml/kg/min, mean +/- SD) was significantly higher than that of IE2 (46 +/- 12 ml/kg/min, N = 9, p < 0.01). The accumulated oxygen deficit of IE1 was not significantly different from the maximal accumulated oxygen deficit (the anaerobic capacity) of the subjects (69 +/- 10 ml/kg/min), whereas the corresponding value for IE2 was less than the subjects' maximal accumulated oxygen deficit (P < 0.01). The peak oxygen uptake during the last 10 s of the IE1 (55 +/- 6 ml.kg-1.min-1) was not significantly less than the VO2max of the subjects (57 +/- 6 ml/kg/min). The peak oxygen uptake during the last 10 s of IE2 (47 +/- 8 ml.kg-1.min-1) was lower than the VO2max (P < 0.01). In conclusion, this study showed that intermittent exercise defined by the IE1 protocol may tax both the anaerobic and aerobic energy releasing systems almost maximally.

The comparison:

IE1 protocol: same as in the 1996 study.

IE2 protocol: 4-5 reps, each rep a 30-second exercise at an intensity of approximately 200% of the subject’s VO2max, with a 2-minute rest.

RESULTS: Although the IE2 group introduced more variables, the key variable was the 2-minute rest.

Apparently, the increased rest in IE2 undermines the benefits of a maximal-intensity workout. In other words, limiting the rest period to 10 seconds is crucial for getting better results.

So-Called Tabata Workouts

As I mentioned at the beginning, most workouts and programs that claim to use the Tabata protocol do no such thing. Many workouts do advocate a 20-second on/10-second off protocol, but they are not maximal-intensity. These workouts can include everything from planks to kettlebells to quick-stepping. All of them might be good workouts. They are just mislabeled as Tabata workouts.

The biggest offenders are those that advocate more than 8 reps. The litmus test is how long a workout lasts. It should be limited to 4 minutes!

I’m tempted to insert a video of one such workout here so you see what a fake Tabata workout looks like. However, there are so many out there that I will leave you to your own devices to hunt them down if you are really interested. Just don’t fall for the Tabata hype. You don’t need a book, a DVD, a yoga mat, kettlebells, or anything else except the equipment necessary for doing a maximal-intensity sprint.

Even just running will do. Or bicycling, rowing, swimming, sprinting up hills or stairs (with care!), jumping rope, or pushing a sled. Avoid running on a treadmill, though. Think about that one.

What can YOU Expect?

A variety of elite athletes in different sports and at different levels have now been studied using the Tabata protocol. Results are consistent across the board.

What if you are not an elite athlete (except maybe in your own mind, like I am)? The good news is that you can still benefit from a ‘near-Tabata’ workout, as Professor Martin Gibala’s research group has discovered for the middle-aged sedentary crowd.

HANG ON … JUST ONE MORE BIT OF SCIENCE

The Gibala protocol for sedentary folks was published in 2011. The reference and abstract are:

REFERENCE:

Hood, M.S., Little, J.P., Tarnopolsky, M.A., Myslik, F., and Gibala, M.J. 2011. Low-Volume Interval Training Improves Muscle Oxidative Capacity in Sedentary Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise 43(10): 1849-1856.

ABSTRACT:

Introduction: High-intensity interval training (HIT) increases skeletal muscle oxidative capacity similar to traditional endurance training, despite a low total exercise volume. Much of this work has focused on young active individuals, and it is unclear whether the results are applicable to older less active populations. In addition, many studies have used “all-out” variable-load exercise interventions (e.g., repeated Wingate tests) that may not be practical for all individuals. We therefore examined the effect of a more practical low-volume submaximal constant-load HIT protocol on skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity in middle-aged adults, who may be at a higher risk for inactivity-related disorders.

Methods: Seven sedentary but otherwise healthy individuals (three women) with a mean +/- SD age, body mass index, and peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) of 45 +/- 5 yr, 27 +/- 5 kg/m2, and 30 +/- 3 mL/kg/min performed six training sessions during 2 wk. Each session involved 10 × 1-min cycling at ca. 60% of peak power achieved during a ramp VO2peak test (eliciting ca. 80%-95% of HR reserve) with 1 min of recovery between intervals. Needle biopsy samples (vastus lateralis) were obtained before training and ca. 72 h after the final training session.

Results: Muscle oxidative capacity, as reflected by the protein content of citrate synthase and cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV, increased by ca. 35% after training. The transcriptional coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha was increased by ca. 56% after training, but the transcriptional corepressor receptor-interacting protein 140 remained unchanged. Glucose transporter protein content increased ca. 260%, and insulin sensitivity, on the basis of the insulin sensitivity index homeostasis model assessment, improved by ca. 35% after training.

Conclusions: Constant-load low-volume HIT may be a practical time-efficient strategy to induce metabolic adaptations that reduce the risk for inactivity-related disorders in previously sedentary middle-aged adults.

Needle biopsy? Yup…these were some serious volunteers!

In case you are getting worn out on all this science-y stuff, the bottom line of this study is that even just 2 weeks of lower-intensity ‘HIT’ (6 workouts, 60% intensity, 10 reps, each rep a 1-minute exercise with a 1-minute rest) can boost the action of several enzymes in muscle metabolism (hence the muscle biopsies).

The icing on the cake in this study was the boost in insulin sensitivity. That is a HUGE benefit!

There you have it. Tabata-style, Gibala-style, whatever you decide to do, keep it simple, don’t overdo it, and get fitter.

I am SO glad, especially for my knees, that I gave up marathons, 10Ks, triathlons, and the like, in exchange for high- and/or maximal-intensity training!

Crucial Fitness Caveat

LONGEVITY. This is the missing component of almost ALL research and advice on fitness. We do have a lot of data on lab animals. If you are a rat, you can find a great workout program that will extend your life.

What about us humans? Research up until recently has had to depend on epidemiological studies – meaning, finding folks who live a long time and seeing what they do in the way of physical activity. This kind of study rests on correlations, not cause and effect. We really have no clue what kind of activities a centenarian followed that led to his or her living to be 100 years old.

A recent change in longevity research, however, has unearthed a genetic variable that supports longevity and can be changed by exercise. This variable is called telomere length. Telomeres are little bits of DNA at the tips of chromosomes. They act like longevity clocks. Longer ones mean longer lifespans; shorter ones mean shorter lifespans.

I will write more on the topic of telomeres at another time, since there are several simple things you can do to boost your own telomeres for greater longevity. For now I will just say that exercise is one of those things. However, some kinds of exercise have a beneficial effect on telomeres, while others have a negative effect.

That’s right. The wrong exercises can shorten your lifespan!

I’m researching this topic for an article to be posted soon. It will be can’t-miss reading for everyone.

All the best,

Dr. D

[…] Achieving Fitness in Less Time. HerbScientist.com. […]